Fact check: Biden says Hamas doesn’t represent Palestinians. Is that true?

Guest Article by Ryan Jones.1, Israel Today2

US President Joe Biden, in addition to providing strong support to Israel, has been at the forefront of a campaign by Western leaders and media to convince everyone that Hamas doesn’t represent the Palestinian public in general.

Biden and others try to paint a picture of Hamas as an isolated, fringe movement that stands in opposition to the more “peaceful” leanings of the majority of Palestinians. But is that true?

On what evidence do Biden and the others base this assessment? It surely isn’t based on surveys of the Palestinian public, or on what the Palestinian masses taking to the streets are chanting.

And if Biden concludes that the masses of Israelis taking to the streets of Tel Aviv every week prior to this war to oppose judicial reform represent the Israeli public in general, then we must also conclude the same of the Palestinians.

So what are the Palestinians telling us?

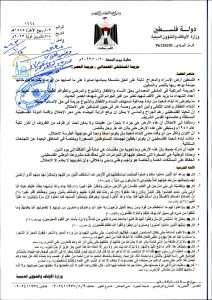

On Friday morning, the Palestinian Authority of Mahmoud Abbas, who Biden tried to meet with this week, published an official government document urging mosques under its jurisdiction to offer sermons that effectively call for the destruction of the Jews.

On Friday morning, the Palestinian Authority of Mahmoud Abbas, who Biden tried to meet with this week, published an official government document urging mosques under its jurisdiction to offer sermons that effectively call for the destruction of the Jews.

The document stressed in relation to the Gaza war that “our Palestinian people cannot raise a white flag until the occupation [sic] is removed and an independent Palestinian state is established with Jerusalem as its capital.”

When it spoke of the Palestinian people being unable to surrender, the PA did not make a distinction between Hamas and the rest of Palestinian society.

More to the point, Abbas’s government included in the official document the old antisemitic Islamic reference (from the Hadith):

“The hour will not come until the Muslims fight the Jews and the Muslims kill them, until the Jew hides behind a stone or a tree and the stone or the tree says, ‘O Muslim, O servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me, come and kill him.’”

The Israeli organization Regavim called the document a clear declaration of war by the Palestinian Authority.

But if Abbas and his regime were hoping to score points by echoing Hamas, survey data shows they failed. The Palestinian public would still prefer to be ruled by Hamas.

Palestinian Media Watch reported on large Palestinian demonstrations in Ramallah, Hebron and Nablus on Wednesday during which the masses chanted: “We want Hamas!” and “The people want to take down [Abbas]!”

PMW also notes that recent student union elections held at Birzeit University in Ramallah and An-Najah University in Nablus were both won by Hamas.

And a July poll taken by the FIKRA forum of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy found that “57% of Gazans express at least a somewhat positive opinion of Hamas—along with similar percentages of Palestinians in the West Bank (52%) and East Jerusalem (64%).”

In other words, if elections were held today, Hamas would win. That’s why elections haven’t been held since 2006, and Abbas is now in the 18th year of a 4-year presidential term.

Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett on Thursday said that even if the international community prefers to close its eyes and plug its ears to the truth, Israelis need to be clear-headed.

Bennett tweeted:

“The truth must be told:

“Most of the residents of Gaza support Hamas, and many of them enthusiastically support the murder of innocent Jews.

“I have heard many times, and recently from various world leaders, the claim that the majority of the population of Gaza is held captive by Hamas and is generally peace-seeking.

“This is simply not true.

“The majority of the Gazan public supports Hamas and its mission to destroy Israel.

“Friends,

“Hamas relies on the broad support of the residents of Gaza.

“Without this support, Hamas could not exist.

“This is the bitter reality.

“One should not conclude from this that Israel will aim to harm civilians.

“This is not our way.

“But we must not lie to ourselves.

“You need to know the truth.”

It is true that Hamas does not represent every Palestinian. We personally know some Palestinian Arabs who are disgusted by Hamas, and who blame the terror group, not Israel, for all their troubles.

But the sad fact is that they are the minority.

Hamas is popular and powerful because the Palestinian public made it that way. The Islamist group could never have grown to what it is now without being planted in fertile soil.

Seventeen years ago, the Palestinian public even voted for Hamas, giving it a solid majority in the Palestinian Parliament. It’s true that half of all Palestinians today either weren’t alive or couldn’t vote back then. But as the survey data, university elections and mass demonstrations referenced above reveal, the next generation is more extreme than their parents.

Unfortunately, this is a problem that probably won’t be solved, even with the military defeat of Hamas in Gaza.

After World War II, the ideologies that fueled the Axis war campaign had to be rooted out at the educational level so that a new Germany and a new Japan could be established. That won’t happen here. Israel isn’t going to try to reeducate Palestinians and root out Islamist ideology from their schools and mosques. And if it tried, the world wouldn’t allow it.

And so we wait for the next ISIS to arise and the next war to come.

Note by Wolf Paul:

The same argument, expressed differently, goes as follows: The Palestinians in Gaza are not responsible for the crimes of Hamas; rather, they are victims. One could say this if there were significant resistance against Hamas in Gaza, if the citizens of Gaza were actively working to drive Hamas out of power. Certainly, there are some who are doing so, but one does not hear muc hfrom them. The silent (and partly cheering) majority in Gaza is just as responsible for the crimes of Hamas as the silent majority in Germany and Austria were complicit in the crimes of the Nazi era. Austria also indulged in playing the victim role for decades; it was only 45 years after the end of the war that the complicity of the Austrians was rightfully and long overdue acknowledged by Chancellor Franz Vranitzky.

This article was originally published by Israel Today.

Copyright ©2023 by Israel Today. Used by permission.

The cover picture by Wisam Hashlamoun shows Palestinians in Hebron/West Bank demonstrating in support of Hamas and its crimes.

- Ryan Jones says about himself, “I am a Gentile Christian from the United States who has lived in Israel since 1996. That was the year that my local church suddenly became aware that Israel was still alive, and her biblical story and mission still ongoing.

It was in Jerusalem that I later met my wife, an Israeli-born Christian of Dutch background whose parents had come to the Jewish state for the same reasons, only several decades earlier.

My wife and I live in the Jerusalem-area town of Tzur Hadassah with our seven children, and we are active members in the local Messianic Jewish community.”

Ryan has served since 2007 as a writer and editor for Israel Today. Before that, he wrote for and was published in a number of other online and print publications dealing with Middle East current events.[↩] - Israel Today is a Jerusalem-based Zionist news agency founded in 1978 to serve you, as you read the Bible in one hand and the news in the other. We bring a biblical dimension to journalism on Israel, the Middle East and the Jewish world. Israel Today appears in English, German and Dutch. Israel Today maintains a diverse staff of local journalists who live in the Land and therefore report from firsthand experience, offering a mix of information, interviews, inspiration and daily life in Israel.

ISRAEL TODAY’S MISSION is to be the definitive source for truthful, balanced, perspectives on Israel; and to provide timely news directly from Jerusalem – the focus of world attention. This is especially important in these times when we see prophetic events unfolding before our eyes.[↩]